Milk ejection causes asynchronous ripples of pressure change throughout the breast stroma

Milk ejection is not machine-like but a wave of pressure changes which ripple throughout the breast

The alveoli glands contract

The lactocytes which line the alveolar lumen are surrounded by star-shaped, oxytocin-sensitive, contractile myoepithelial cells. The myoepithelial cells are enveloped by a thin but dense collagen basal membrane.

When oxytocin is released in response to nipple stimulation, myoepithelial cells contract, although not all myoepithelial cells contract in response to a pulse of oxytocin, and alveoli are not uniformly dilated or contracted at any one time. Contraction of alveolar myoepithelial cells results in contraction of the alveolus and its lumen, ejecting milk into the ducts.

Stewart et al’s 3D imaging of mice mammary glands found that lactocytes contracted by about a third, repetitively and unpredictably warping and stretching under the stochastic contractile mechanical pressure of the myoepithelial cells in response to a pulse of oxytocin.9

The mammary ducts shorten and dilate

Similarly, the cuboidal epithelial cells which line the lactiferous ducts are surrounded by myoepithelial cells, again enveloped by a basal membrane.

-

Contraction of ductal myoepithelial cells results in shortening and dilation of ducts, minimising resistance to milk flow.10

- Dilation may be augmented by intralumenal pressure of flow from the alveoli.

-

Main ducts dilate by 0.5 - 1.9 mm in diameter.

-

Ductal dilation may last 45 seconds - 3.5 minutes.

-

A 2 - 8 second difference has been observed between the initial oxytocin burst and the timing of flow in main ducts. That is, ductal dilation is also, like alveolar contraction, asynchronous.

-

Contraction of myoepithelial cells surrounding alveoli which are less full may result in lower intraductal pressure and smaller duct dilation.

Patterns of human milk ejection are innately programmed and robust

Most milk ejections are not felt by women, and some women don’t feel milk ejections at all.7 But human milk ejection patterns are innately programmed and physiologically robust.

-

Duct diameter changes during milk removal from a healthy breast are stable and do not relate to the infant’s milk intake, time to milk ejection, time since last breastfeed, stage of lactation, or milk production.

-

An individual mother’s timing, pattern and number of milk ejections is consistent over time and between lactations, whether breastfeeding or pumping.11-13

The number of milk ejections during a breastfeed is highly variable between successfully breastfeeding mothers, and is the only factor related to the amount of milk the infant consumes for that breastfeed, regardless of the length of feed.

-

Many milk ejections can occur in a short period of time: between one and 17 episodes of increased intraductal pressure have been measured in breastfeeds of up to 25 minutes.11

-

The median time from the end of one milk ejection to the beginning of the next is 90 seconds, with a range of 40-203 seconds.

-

The first milk ejection contributes a greater volume and greater total percentage of milk expression than each subsequent milk ejection.

-

The first two milk ejections in a feed produce 62% of total milk removal in a 15 minute period.

In summary, the stroma of the lactating breast is exposed to irregular alterations of pressure gradients, which depend on frequency of milk removal. Milk ejection is asynchronous across the breast, with heterogenous emptying of alveoli and lobules. Because both alveoli contraction and milk duct dilatation occur asynchronously in response to oxytocin impulses, milk flows from different parts of the breast, heterogeneously.

Intralobular stroma is exposed to frequent and irregular alterations in pressure gradients due to alveolar contractions and ductal dilatations

Inter-lobular stroma is dense fibrous connective tissue, in which adipose tissue is embedded. Adipose tissue is highly variable within breasts and is mostly not interspersed with glandular tissue.3-6

The intra-lobular stroma in the lactating mammary gland is a loose but highly vascular connective tissue, highly responsive to mammary epithelial signals.23 Intra-lobular stroma also contains fibroblasts, abundant lymphocytes, macrophages, and lymphatic vessels.

The resting stromal density and tension exerted on lactiferous ducts and lymphatic vessels varies from woman to woman, influenced by genetic predispositions.3 Arterial capillaries lace closely around the basement membrane of the alveoli. This proximity allows oxygen, proteins, and nutrients to diffuse into the lactocytes, and carbon dioxide, unused proteins, and some waste products to diffuse from the alveoli back into venous capillaries.

The lymphatic vasculature regulates interstitial pressures in the stroma of a lactating breast

During lactation, half of the lymphatic vessels are collapsed at any one time, though Jindal et al observed that in the weeks immediately after weaning, all lymphatic vessels are dilated and contain cellular debris.3

Seventy-five percent of mammary lymph drainage is superficial or cutaneous, draining into the axillary nodes; the other 25% is in the deep tissue, particularly of the medial breast, draining into the internal mammary nodes.

-

Ninety percent of the arterial blood carried into the mammary gland returns to the venous circulation

-

10% diffuses out of the capillaries into the stroma, as interstitial fluid.

New research in other parts of the human body show that lymphatic vasculature downregulates local inflammation through multiple pathways, including through removal of inflammatory products and lymphangiogenesis. The NDC mechanobiological model of breast inflammation proposes that lymphatic vasculature is another complex adaptive system within the lactating breast immune system.24-27

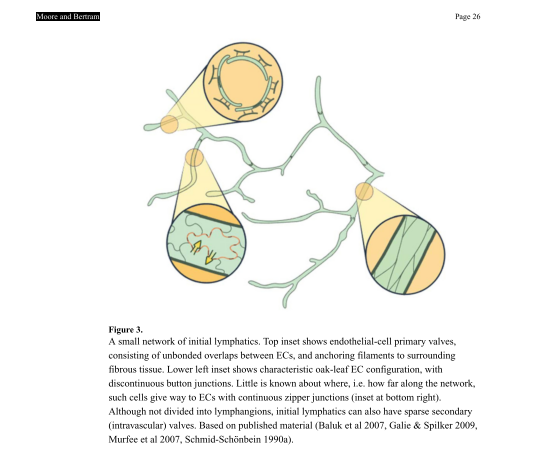

Blunt-ended lymphatic capillaries are composed of a single layer of specialised lymphatic endothelial cells with sparsely intermittent valves. The capillaries are anchored by filaments to the stroma and are sensitive to pressure dynamics. Their sparse basement membrane and discontinuous intercellular junctions (known as buttons) allow passive intake of interstitial fluid, forming intra-vascular lymph.

In addition to diffusion of fluid from the higher pressure of the stroma into the lymphatic capillary, entities too large to cross back through the tight junctions of venous capillaries pass through the large button junctions. These 'waste' entities include cell debris, protein complexes, lipids, macromolecules, immune cells, and bacteria.

Lymphatic capillaries are sensitive to contextual signals and have the capacity to tighten up intercellular junctions and limit transport of fluid and macromolecules. In response to increased interstitial fluid load and inflammatory mediators, lymphatic vessels adapt their pumping activity to increase or decrease transport, regulating the inflammatory state of the tissue they drain.24-27

Lymph then moves under pressure gradients from the lymphatic capillaries into lymphatic collection vessels, which have a basement membrane, valves, and lymphatic muscle cells.

-

Lymphatic collection vessels are intrinsically contractile, and pump lymph towards the lymph nodes.

-

Extrinsic pumping by pressure changes in surrounding tissues also contributes.24-27

-

Pectoral muscle movement and the movement of breathing are likely to play only a minor role in lymph movement.

The NDC mechanobiological model of breast inflammation hypothesises that two dominant sources of breast tissue and stromal movement support extrinsic pumping of lymph

-

The vibratory effects of gravity acting on the breast

-

The dynamic and variable pressure gradients formed across stromal tissue by repetitive, irregular, and widespread alveolar contractions and lactiferous duct dilations.

One-way valves direct the flow of lymph towards the lymph nodes, where it is filtered in preparation for return into the blood stream.

Figure below: Moore & Bertram 2018. Unbonded overlap between endothelial cells and filamentous anchoring in stroma

Selected references

Comprehensive citations are found in the two research publications which the breast inflammation module is built (Douglas 2022 mechanobiological mode; Douglas 2022 classification, prevention, management; Douglas 2023)

Douglas P. Re-thinking benign inflammation of the lactating breast: a mechanobiological model. Women's Health. 2022;18:17455065221075907.

Douglas PS. Re-thinking benign inflammation of the lactating breast: classification, prevention, and management. Women's Health. 2022;18:17455057221091349.

Douglas PS. Does the Academy of Breastfeeding Medicine Clinical Protocol #36 'The Mastitis Spectrum' promote overtreatment and risk worsened outcomes for breastfeeding families? Commentary. International Breastfeeding Journal. 2023;18:Article no. 51 https://doi.org/10.1186/s13006-13023-00588-13008.

Uvnäs Moberg K, Ekström-Bergström A, Buckley S, Massarotti C, Pajalic Z, Luegmair K, Kotlowska A, Lengler L, Olza I, Grylka-Baeschlin S, Leahy-Warren P, Hadjigeorgiu E, Villarmea S, Dencker A. Maternal plasma levels of oxytocin during breastfeeding-A systematic review. PLoS One. 2020 Aug 5;15(8):e0235806. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0235806. PMID: 32756565; PMCID: PMC7406087.

- Kent JC, Gardner H, Lai C-T, Hartmann PE, Murray K, Rea A, et al. Hourly breast expression to estimate the rate of synthesis of milk and fat. Nutrients. 2018;10:1144.

- Kent JC, Gardner H, Geddes DT. Breastmilk production in the first 4 weeks after birth of term infants. Nutrients. 2016;8(756):doi:10.3390/nu8120756.

- Jindal S, Narasimhan J, Vorges VF, Schedin P. Characterization of weaning-induced breast involution in women: implications for young women's breast cancer. Breast Cancer. 2020;6(55):https://doi.org/10.1038/s41523-020-00196-3.

- Ramsay DT, Kent JC, Hartmann RA, Hartmann PE. Anatomy of the lactating human breast redefined with ultrasound imaging. Journal of Anatomy. 2005;206:525-34.

- Murase M, Mizuno K, Nishida Y, Mizuno H. Comparison of creamatocrit and protein concentration in each mammary lobe of the same breast: does the milk composition of each mammary lobe differ in the same breast? Breastfeeding Medicine. 2009;4(4):189-95.

- Gardner H, Kent JC, Hartmann PE, Geddes DT. Asynchronous milk ejection in human lactating breast: case series. Journal of Human Lactation. 2015;31(2254-259).

- Ramsay DT, Kent JC, Owens RA, Hartmann PE. Ultrasound imaging of milk ejection in the breast of lactating women. Pediatics. 2004;113:361-7.

- Geddes DT. The use of ultrasound to identify milk ejection in women - tips and pitfalls. International Breastfeeding Journal. 2009;4(5):doi:10.1186/746-4385-4-5.

- Stewart TA, Hughes K, Stevenson AJ, Marino N, Ju AL, Morehead M, et al. Mammary mechanobiology - investigating roles for mechanically activated ion channels in lactation and involution. Journal of Cell Science. 2021;134:doi:10.124/jcs.248849.

- Mortazavi N, Hassiotou F, Geddes DT, Hassanipour F. Mathematical modeling of mammary ducts in lactating human females. Journal of Biomechanical Engineering. 2015;137(7):071009.

- Prime DK, Geddes DT, Hepworth AR, Trengove NJ, Hartmann PE. Comparison of the patterns of milk ejection during repeated breast expression sessions in women. Breastfeeding Medicine. 2011;6(4):183-90.

- Gardner H, Kent JC, Prime DK, Lai C-T, Hartmann PE, Geddes DT. Milk ejection patterns remain consistent during the first and second lactations. American Journal of Human Biology. 2017;29:e22960.

- Gardner H, Kent JC, Lai CT, Geddes DT. Comparison of maternal milk ejection characteristics during pumping using infant-derived and 2-phase vacuum patterns. International Breastfeeding Journal. 2019;14(47):https://doi.org/10.1186/s13006-019-0237-6.

- Kent JC, Mitoulas LR, Cregan MD, Ramsay DT, Doherty DA, Hartmann PE. Volume and frequency of breastfeedings and fat content of breast milk throughout the day. Pediatics. 2006;117(3):e387-e95.

- Kersin SG, Ozek E. Breast milk stem cells: are they magic bullets in neonatology? Turkish Archives of Pediatrics. 2021:doi:10.5152/TurkArchPediatr.2021.21006.

- Witkowska-Zimny M, Kaminska-El-Hassan E. Cells of human milk. Cellular and Molecular Biology Letters. 2017;22(11):doi:101186/s11658-017-0042-4.

- Ninkina N, Kukharsky M, Hewitt MV. Stem cells in human breast milk. Human Cell. 2019;32:223-30.

- Li S, Zhang L, Zhou Q. Characerization of stem cells and immune cells in preterm and term mother's milk. Journal of Human Lactation. 2019;35(3):528-34.

- Hassitou F, Hartmann PE. At the dawn of a new discovery: the potential of breast milk stem cells. Advances in Nutrition. 2014;5:770-8.

- Yamauchi Y, Yamanouchi I. Breast-feeding frequency during the first 24 hours after birth in full-time neonates. Pediatrics. 1990;86(2):171-5.

- Okechukwu A, A O. Exclusive breastfeeding frequency during the first seven days of life in term neonates. Nigerian Postgraduate Medicine Journal. 2006;13(4):309-12.

- Hill PD, Aldag JC, Chatterton RT, Zinaman M. Primary and secondary mediators' influence on milk output in lactating mothers of preterm and term infants. Journal of Human Lactation. 2005;21(2):138-50.

- Hassiotou F, Geddes DT. Anatomy of the human mammary gland: current status of knowledge. Clinical Anatomy. 2013;26:29-48.

- Oliver G, Kipnis J, J RG, Harvey NL. The lymphatic vasculature in the 21st century: novel functional roles in homeostasis and disease. Cell. 2020;182:270-96.

- Schwager S, Detmar M. Inflammation and lymphatic function. Frontiers in Immunology. 2019;10:doi:10.3389/fimmu.2019.00308.

- Steele MM, Lund AW. Afferent lymphatic transport and peripheral tissue immunity. The Journal of Immunology. 2021;206:264-72.

- Moore JE, Bertram CD. Lymphatic system flows. Annual Review of Fluid Mechanics. 2018;50:459-82.