Lactogenesis: secretory differentiation and activation of the human mammary gland

Lactogenesis

Colostral milk is first secreted into the developing alveoli lumens and lactiferous ducts between 16-22 weeks gestation (on average about 20 weeks), marking the beginning of lactogenesis. Some researchers place this as early as 12 weeks gestation.

-

In 1969, in the first definition of lactogenesis, Folley wrote that "… in most species [lactogenesis] may be broadly defined as the initiation of a copious flow of milk at or about the time of parturition".

-

The terms lactogenesis I and lactogenesis II were used up until the 2000s, but are "at best non-descriptive and at the worst misleading as they imply that the initiation of lactation has two beginnings rather than being a cascade of events." Pang and Hartmann 2007 p. 212

-

Here we use the terms secretory differentiation and secretory activation to describe lactogenesis, as recommended by Australian researcher Professor Peter Hartmann and his teams' international collaborators in that same 2007 publication.

Slide 23 in Dr Kate Rassie's talk on Diabetes, PCOS and breastfeeding is an excellent illustration of the time frames of mammogenesis, lactogenesis, and galactopoiesis, found here.

Secretory differentiation

Secretory differentiation is the first stage in the progression towards the synthesis and secretion of milk, which occurs during pregnancy.

The primary preparatory hormones include oestrogen, progesterone, prolactin, and placental lactogen. These hormones induce the physiological transition of the mammary gland from a non-secreting branched tissue into a highly active secreting organ comprised of a complex network of ducts and alveoli, grouped into seven to ten lobes in humans.

The remodelling of the mammary gland tissue which occurs during early pregnancy includes

-

Epithelial proliferation

-

Side-branching of ducts

The development of the mammary gland does not occur in neat lobules which can be anatomically delineated in imaging or surgery, but is an intertwined tangle of ducts and alveoli.

After the early morphological changes of pregnancy, alevolar cells increase the expression of lactogenic genes, which differentiate them into lactocytes. Subsequently, there is

-

Differentiation of the mammary epithelial cells into lactocytes with the capacity to synthesise milk constitutents such as lactose, casein, alpha-lactalbumin, fatty acids.

-

Development of thousands of alveolar structures which branch off the central ductal epithelium in lobular clusters. Alveoli contain a bilayer of lactocytes surrounded by myoepithelial cells, with a central lumen into which milk is secreted.

-

The mammary gland cellular composition differentiates, including mammary epithelial cells (luminal or ductal, alveolar, and myoepithelial) and mesenchymal or stromal cells which include adipocytes, fibroblasts, endotheial cells (of blood and lymph vessels) and macrophages.

The rapid expansion of ductular-lobular-alveolar system during pregnancy results in increased breast volume. The production of milk begins as early as a few weeks into the second trimester – that is, from about 15 weeks. However, high progesterone and estrogen levels inhibit the milk-forming action of prolactin, as does the placental lactation inhibition hormone.

Colostrum

The first fluid produced is colostrum, which can often (though not always) be manually expressed in the third trimester of pregnancy. Colostrum is also produced in small quantities in the first few days post-birth, perhaps 30 mls in 24 hours.

Colostrum contains high concentrations of immunological components such as secretory IgA, lactoferrin, and leucocytes as well as developmental factors such as epidermal growth factor.

The concentration of lactose, the most osmotically active component in breast milk, is low in colostrum, which explains the low volume of colostrum, and indicates that the primary function of colostrum is immunological rather than nutritional.

Secretory activation

Secretory activation is the initiation of copious milk secretion. Research shows that it occurs normally between one and five days postpartum.

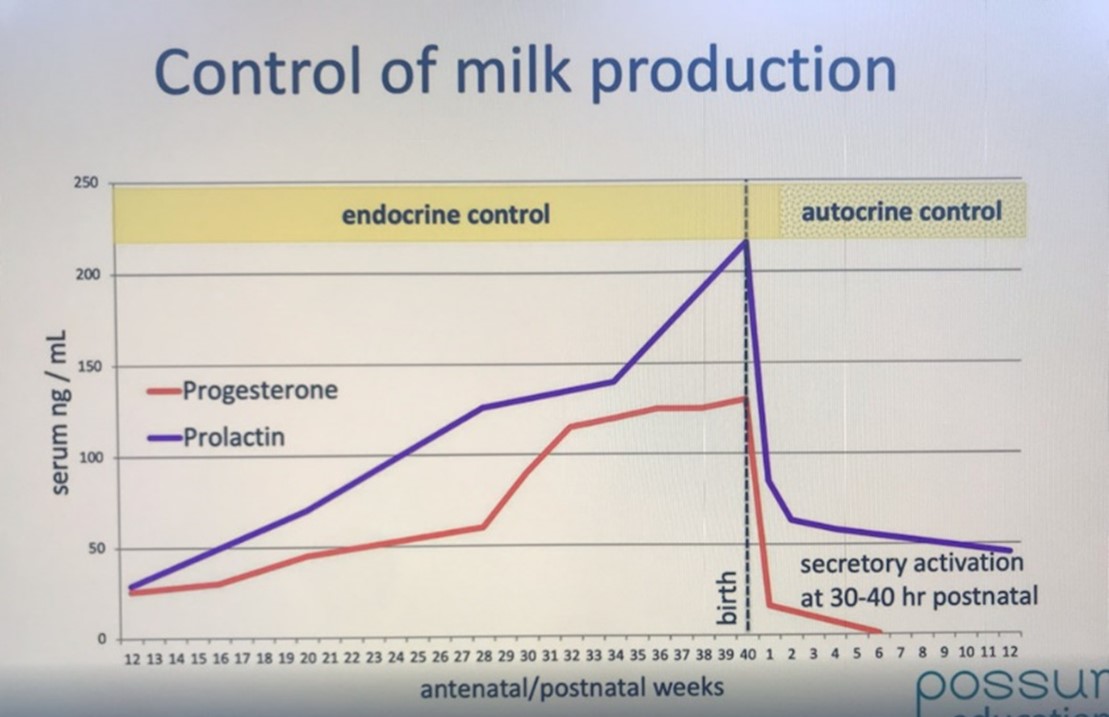

Milk synthesis is inhibited antenatally by high levels of progesterone, oestrogen and placental lactogen.

Acknowledgement: The image below is copied from Dr Sharon Perrella's talk, NDC Breastfeeding Masterclass #3.

With the birth, the progesterone, oestrogen, and prolactin levels drop suddenly.

-

24 hours after the birth, the amount of progesterone in the bloodstream has plummeted dramatically. The fall in progesterone levels allows prolactin to exert its effect and the lactocytes to secrete milk.

-

By 30 or 40 hours after delivery of the placenta, the amount of prolactin and oestrogen in the bloodstream has also plummeted.

You can find out about other hormones which are required for ongoing mammary cell proliferation here.

Transitional milk

In response to these profound hormonal changes of parturition, by 30-40 hours post-birth

-

The basement membranes under the lactocytes have tightened up to become impermeable.

-

The tight junctions between the lactocytes have closed shut. Closed tight junctions limit the passage of ions like sodium and chloride and small molecules.

Compared to colostrum, the transitional milk which forms in the alveoli after tight junction closure, has

-

Increased lactose concentrations

-

Increased sodium, chloride, and magnesium concentrations

-

Decreased potassium and calcium concentrations.

Milk production is established by two weeks postpartum. By one month, transitional milk has become mature milk.

Although there is a dramatic shift in composition of breast milk during the first month post-birth, the concentration of macronutrients in breast milk remains relatively constant over the course of lactation, with gradual increases in milk fat content over the course of one feeding. You can find out about galactopoiesis here.

The mammary gland synthesizes almost all milk components, including fatty acids. However, longer-chain fatty acids (over 16 carbons) in milk are primarily derived from the maternal diet and adipose tissue, rather than being synthesized entirely within the mammary gland.

Pathways of milk secretion

Transcellular

Neville was the first to subdivide the transcellular pathway of milk section (which occurs across the lactocytes) into

-

Exocytosis from Golgi derived secretory vesicles (milk specific proteins such as casein micelles, alpha lactalbumin, lactoferrin), lactose oligosaccharides, citrate, calcium, phosophate

-

Milk fat globule secretion

-

Ions, glucose, calcium, and water across the apical membrane

-

Pinocytosis-exocytosis of immunoglobuline, insulin, other protein hormones.

Paracellular

Neville also explicated the paracellular pathway, which is relatively permeable during pregnancy and during mastitis but relatively impermeable during normal lactation. There remains a limited paracellular diffusion of blood components, including leukocytes, sodium, and plasma proteins, into the alveolar lumen during galactopoiesis.

The composition of human milk and its secretion will be discussed in another Lactation module.

Acknowledgement: The image from Spatz et al 2024 p 258 Figure 1 Hormonal changes and daily milk production in the peripartum period was adapted by Spatz et al from Medela with consent.

Selected references

Anderson SM, Rudolph MC, McManaman JL, Neville MC. Key stages in mammary gland development. Secretory activation in the mammary gland: it’s not just about milk protein synthesis! Breast Cancer Res 2007;9(1):204.

Boyle ST, Poltavets V, Samuel MS. Mechanical signaling in the mammary microenvironment: from homeostasis to cancer. In: Birbrair A, editor. Tumor Microenvironment Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology. 1329. Cham.: Springer; 2021. p. https://doi.org/10.1007/1978-1003-1030-73119-73119_73119.

Folley SJ. Symposium on lactogenesis: chairman’s introduction. In: Reynolds M, Folley SJ, editors Lactogenesis: the initiation of milk secretion at parturition. Philadelphia: Pennsylvania Press; 1969. p. 1–3.

Geddes DT, Gridneva Z, Perrella SL, Mitoulas LR, Kent JC, Stinson LF, et al. 25 years of research in human lactation: from discovery to translation. Nutrients. 2021;13:1307.

Lee S, Kelleher SL. Biological underpinnings of breastfeeding challenges: the role of genetics, diet, and environment on lactation physiology. American Journal of Physiology - Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2016;311:E405–E422.

Pang WW, Hartmann PE. Initiation of human lactation: secretory differentiation and secretory activation. Journal of Mammary Gland Biology and Neoplasia. 2007;12:211-221.

Ramsay DT, Kent JC, Hartmann RA, Hartmann PE. Anatomy of the lactating human breast redefined with ultrasound imaging. J Anat 206: 525–534, 2005.

Spatz D, Rodriguez SA, Benjilany S. Having enough milk to sustain a lactation journey: a call to action. Nursing for Women's Health. 2024;28(4):256-262.